Gatekeepers of the top five

Recently, John List posted this on Twitter:

John, who has been a Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago since 2005, is an editor of the Journal of Political Economy—one of the top 5 economics journals—and has held numerous other editorial roles throughout his very successful career.

This success has been, in many ways, unprecedented. Very few graduates of the University of Wyoming (for example), who start their academic careers at the University of Central Florida, become “John Lists of the profession.”

But I digress. A point I am trying to make here is that John knows “how the sausage gets made” in academia, and unlike quite a few others in a similar position, is willing to share the truth—even if that’s the hard truth—with others.

That tweet of his is a case in point. And I have decided to use it to motivate this post. I ask a seemingly trivial question. Who are the editors of the top 5 economics journals? But what I am really asking is: How concentrated is the editorial power at these journals?

The answer to this question is interesting in and of itself, and important for reasons outlined in John’s tweet. If the editors come from just a few schools, then very few academics, especially early career researchers, will have the opportunity to impress them during a seminar talk, for example.

My co-authors and I asked this question—albeit looking at a larger pool of top economics journals—a couple of years ago, and found some striking answers, which we summarized in a short article published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.

There we considered all editors (i.e., including associate editors who, often, have the role of “super reviewers” only, and members of editorial boards).

In this post, I focus on decision-making editors, the so-called gatekeepers, of the top 5 economics journals.

As of mid-2023, there are a total of 48 editors across the five journals. These 48 editors represent 24 institutions around the globe. Well, sort of. Globe here is pretty much defined as the USA (39 editors) and Europe (9 editors).

The following map shows the geographic locations (and the institutional concentration) of the editors. In addition, the map shows the geographic centroid of each journal.

Except for two universities, Chicago and Harvard, there are at most two editors of the top 5 journals from any given institution.

The centroids pinpoint the geographic locations that minimize the average distance from the locations of the institutions where the journals’ editors are.

More on this later. But for now, let’s also take a look at the same data from another angle. The following Sankey plot brings more detail to the picture.

Let’s consider the foregoing two graphs in conjunction. On the map, the QJE centroid is located where Harvard is located. All editors of QJR are Harvard-affiliated, of course.

A comparable, but not similar, story with JPE (as we will see below, this is a new development for JPE). On the other hand, REStud is “located” in the Atlantic, owing to a geographically diverse set of editors from both sides of the Ocean.

AER and Econometrica are similar to the REStud in that they also source their editors from various universities; however, they are different from REStud in that most of their editors come from the USA.

As noted above, the journal centroids presented on the map are the geographic locations that minimize the average distance to locations where the editors’ daytime jobs are.

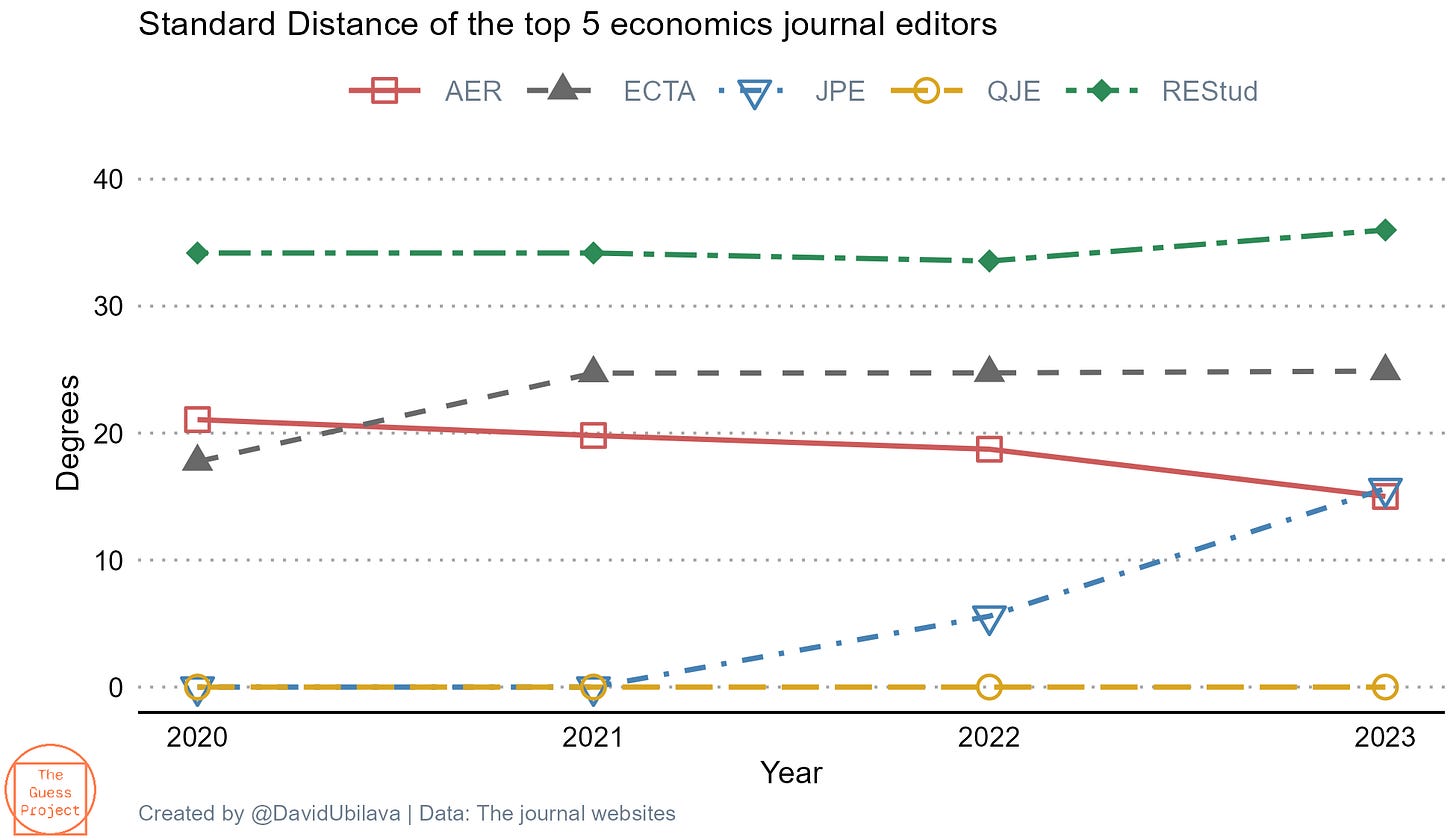

So, what are these distances—the so-called standard distances—for each journal? The following figure answers this question.

In fact, the figure does a bit more than that. Until now, we were looking at the 2023 snapshot. In this figure, we observe the recent trends.

And there have been trends. JPE, in particular, went from being a QJE-like journal (all editors from the same place) to an AER-like journal (at least based on this measure of geographic diversity). REStud has been, historically, the most geographically diverse top five journal. AER has been trending downward, but the slope of this trend is not as dramatic as the upward trend of the JPE.

Speaking of diversity and trends: What is the gender composition of editors at the top five economics journals? Up until this year, REStud had a 50/50 split. QJE has had one women editor, and that has not changed in the past few years. JPE and Econometrica are trending positively (from 2020 zero women as editors).

This post presents a 2023 snapshot and some recent trends about the editors of the top five economics journals. The journals that define the climate of the economics profession tend to be run by scholars from the top universities in the field. Nothing scandalous in this.

But the issue is not in “what is,” rather it is in “what is not.” That the top five economics journal editors come from five countries—with more than 80 percent from just one country—and that more countries and regions are not on the map of editors might be seen as an issue. That no more than just over 25 percent of the top five economics journal editors are women, is an issue.

Setting these issues aside, and if I may refer to John List’s tweet again, one can publish—and people publish—great works in other journals. So, publishing in the top five is not a panacea. Except, when it sort of is.

When “outsiders” publish in one of the top five journals, that is a big deal. A huge deal, really. Indeed, because they are not at a top-ranked university, publishing in a top five journal is one of the strongest signals they may have at their disposal.

And I digress, again. This seems to be a topic for another day. I will say (and show) more when I have more to say (and to show).

Great post with some fascinating data, thanks David!