It’s that time of that year when climatologists predict the possible arrival of El Nino and everyone else says why it may be bad news for [enter a sector, or a country, or about anything else you can think of].

El Nino means “the boy” in Spanish. Peruvian fishermen coined the term, after the Christ child, as they occasionally observed unusually warm waters toward the end of a calendar year. Those are known as the El Nino years. There are also years with unusually cool waters toward the end of a calendar year. Those are known as La Nina (“the girl”) years.

El Ninos and La Ninas occur semi-periodically, over a span of several years. They may re-occur in back-to-back years (more often La Ninas do that), immediately follow one another (more often La Ninas follow El Ninos), or be temporally separated by neutral years.

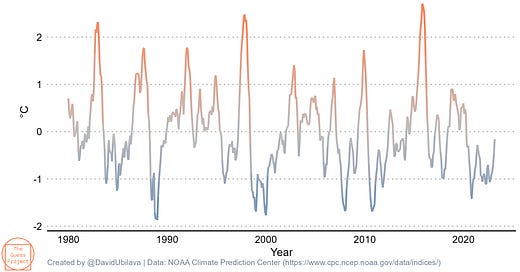

The following graph features this all. Positive deviations in the sea surface temperatures indicate El Ninos; negative deviations — La Ninas. Since the beginning of the 1980s, there were three major El Nino events: the 1982-83 El Nino, the 1997-98 El Nino, and the 2015-16 El Nino.

What happens during the El Nino years? Well, the equatorial Pacific warms up more than usual. But there is more than that. Unlike Las Vegas, what happens in the Pacific doesn’t stay in the Pacific.

During El Nino years weather patterns change in certain parts of the world. As the trade winds weaken across the Pacific, which is what happens as El Nino manifests itself, Southeast Asia and Australia experience droughts and higher-than-usual temperatures, and Central and South Americas experience excessive rainfall and floods, while cooler temperatures are observed in the temperate regions of the Americas. This National Geographic article explains El Nino and its climatic effects neatly.

Because El Ninos cause such significant changes in weather patterns, it is reasonable to expect that it will have an impact on economic outcomes. Agricultural production, of course, is the key suspect.

Lots of studies have examined the agricultural impacts of El Nino events. Earlier studies focused on select countries or larger regions. More recent studies look at smaller regions and subregions. The general consensus is largely unequivocal—El Ninos (and La Ninas) can harm agricultural production through their impact on key weather variables.

So, El Nino can be bad news for regions where its effects are felt. But does this have global implications? Perhaps, but mostly in instances where much of the world’s production is geographically concentrated (e.g., palm oil in Malaysia and Indonesia), or when El Nino results in simultaneous crop failure across geographically separated regions.

A way to gauge the global economic impact of El Nino is by observing commodity price dynamics in response to deviations in the sea surface temperatures, which is, in effect, a measure of the intensity of El Nino and La Nina. I did that a few years ago in my AJAE article. The key takeaway from that work is that yes, the sea surface temperature anomalies impact, somewhat, the dynamics of some commodity prices, but this impact often is regime-dependent (i.e., may or may not happen, depending on a range of factors), and moreover, changes in the sea surface temperatures almost never aid us to make more accurate forecasts of the commodity prices (copra and coconut oil, which are mostly produced in Philippines, Indonesia, and India—all El Nino affected regions—were the only exceptions).

So, circling back to the opening paragraph of this post: Is upcoming El Nino bad news for commodity prices? My answer is: probably not, and certainly not yet. Why not? Because of the three “if’s”:

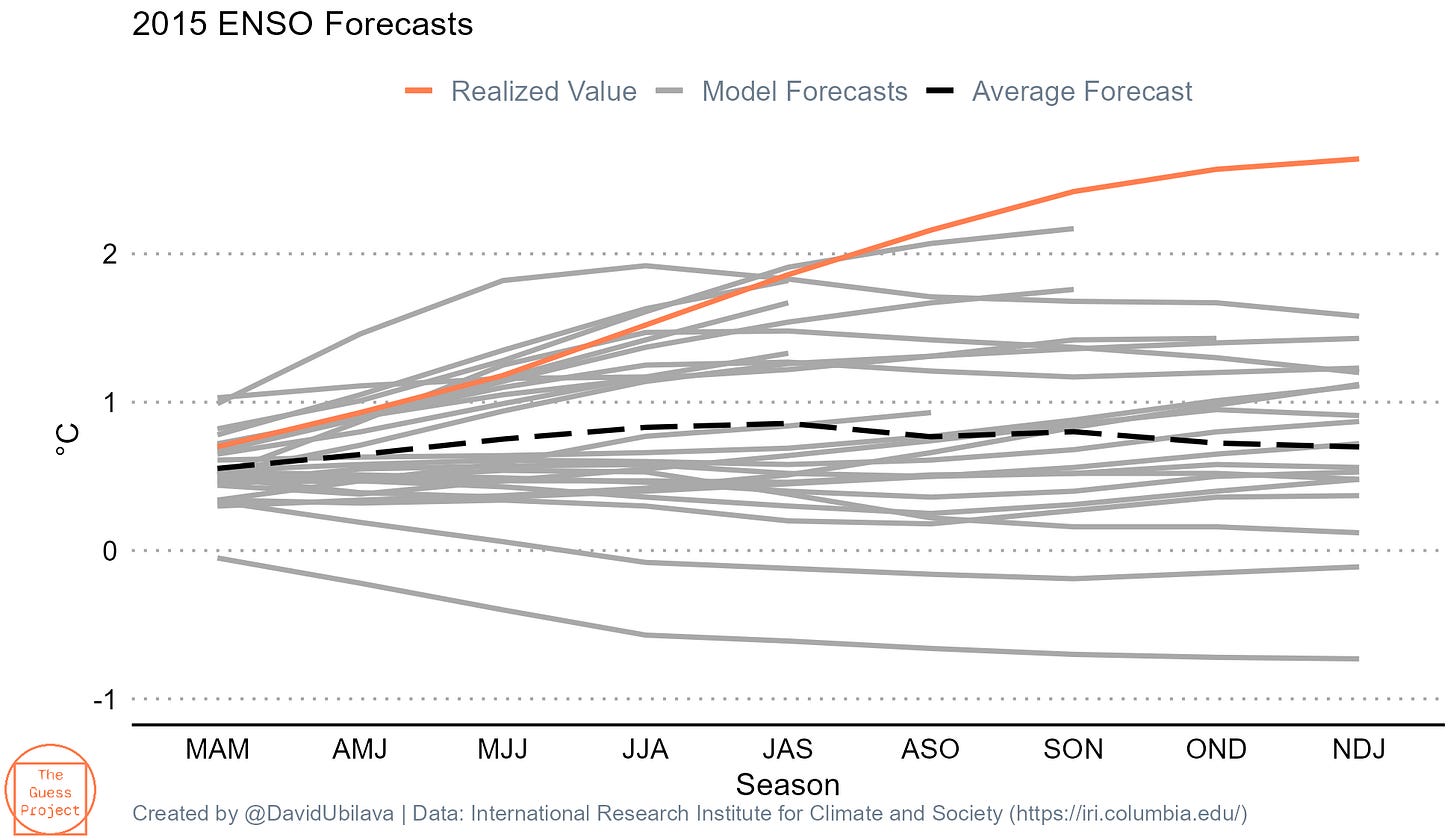

We are in the “spring barrier” so we don’t quite know if El Nino will, indeed, manifest itself as the year progresses. Below is the graph with current projections from a range of different models. The horizontal axis features three-month seasons, starting from March-April-May and ending with November-December-January. The gray lines indicate forecasts from different models. The dashed line indicates the average of the projections.

So, there seems to be a fair bit of support for the upcoming El Nino. Let’s have a look at how similar projections made in the same season played out in previous years. The projections largely underestimated what turned out to be the “super-El Nino” of 2015 (the colored line indicates the realized values):

On the other hand, the projections severely overestimated (indeed missed the La Nina) the “non-El Nino” of 2017:

So, is El Nino coming in 2023? Probably. But it still is anyone’s guess.

And even if El Nino does happen, will it affect weather in parts of the world that are major producers of certain commodities? Chances are it will. But, also, there are no guarantees.

And even if El Nino results in unfavorable weather patterns in these crucial parts of the world, will this effect be strong enough and synchronized enough to cause global commodity shortages and price spikes? Historically, the effect, if any, has been modest. To put things into perspective, when the Russian-Ukraine war erupted, more than a quarter of world wheat exports “disappeared”—what turned out to be for a brief few months—from the global market. That caused about a 70 percent spike in wheat prices. It is very unlikely for an El Nino to generate a global shock of such magnitude.

There are just too many “if’s” to make a conclusive claim at the moment.